Some simulators are useful. They help us predict the weather or train pilots before putting them into real planes. In science, simulators are used to make predictions that inspire experiments. But are simulators necessary for science?

Science depends on real-world data. Few would disagree, scientist or not. But many scientists detest simulations. And outside of science, the word “simulator” conjures images of fake cockpits or VR headsets instead of mathematical equations. If we do choose to simulate something, data needs to be gathered anyway to verify the simulation. So why simulate at all? Just analyze the data.

The difference between a simulation and a model is important. Underlying any simulation is a model. If the simulation is the realization of mechanisms over time, then the model is the collection of those mechanisms. But we can build a model without ever simulating it. Instead, the model can be analyzed mathematically. We can also just look at the model and agree or disagree with the way a mechanism works in the model. That would be based on our prior knowledge and believes about the process that the model attempts to imitate.

How does science work without a model? In the randomized controlled trial, scientists can establish causes and effects by controlling a treatment variable. The effect of the treatment on the outcome is measured by randomly assigning values to the treatment variable and observing outcome variables. But this requires full control of the treatment variable. This mode of science does not require a model. It depends on controlling and observing. But what if control is impossible and we can only observe?

If we can only observe, a model is necessary. Causal inference is the science of making causal claims from observations and it requires what is called a structural causal model. But structural causal models are not simulated. Instead, they are collections of our causal assumptions. They thereby constrain what causal relationships are inferable given observational data and which ones are not. But structural causal models only work if the causality goes in one direction. If the effect also has causal influence on the cause, the structural model becomes virtually useless for inference.

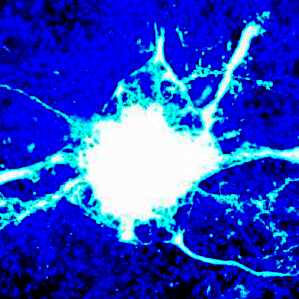

If causality goes both ways, the only solution is to simulate. Consider for example the predator-prey model, where Lynxes eat Hares. The predators influence the prey population by eating them, the prey influence the predator population by nourishing them, and each population controls its own growth rate by procreation. To quantify the causal role of a third population in this system we must simulate. Even if we could measure all three populations at the same time repeatedly for several years. We could of course calculate the correlation coefficients, the partial correlation coefficients and the Granger causality. But because the predator-prey system oscillates, all of these are just approximations of causality that depend on the frequency we can measure at.

The best way to estimate the causal role of the third population is to simulate. Simulate multiple times with different values for the causal parameters and see which causal parameters are most likely to generate the data observed in the wild. Therefore, science needs simulators.

Leave a comment